Culture May Identify Difference, But It Does Not Make Us Different: Visiting Costa Rica’s Cabecar Indigenous Tribe In Quetzal

Article last updated on June 25, 2019. Note that an old date may indicate that an update is not required, not that the text is outdated.

Article written by Nikki Solano

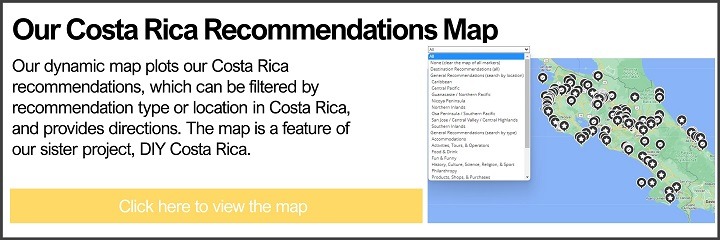

Nikki is the CEO of Pura Vida! eh? Inc. (Costa Rica Discounts), the creator and narrator of Spotify's Costa Rica Podcast with Nikki Solano, and the author of the guidebooks Moon Costa Rica (2019, 2021, 2023, and 2025 editions) and Moon Best of Costa Rica (2022 edition) from Moon Travel Guides. Together with her Costa Rican husband, Ricky, she operates the Costa Rica Travel Blog, created the online community DIY Costa Rica, built the Costa Rica Destination Tool, and designed the Costa Rica Trip Planning 101 E-Course. In addition, Nikki has written about or presented Costa Rica on Rick Steves' Monday Night Travel show and podcast/radio show, in Wanderlust Magazine, and for Essentialist. Want to show your appreciation for her free article below? Thank Nikki here. ❤️️

UPDATE: Since writing the blog post below, we have created a donation project aimed at benefiting the children of some of Costa Rica’s indigenous communities. Please read more about our donation (and plans to continue donating in the future) here: Thank You Readers And Travellers For Making This Happen. We Could Not Have Done It Without You.

All in Quetzal is quiet. At least a 2 hour drive from the nearest city (Turrialba) and in the heart of the jungle, this tiny town consisting of a high school, elementary school, and a few houses is the core of the Cabecar tribe’s development. Although some onlookers would view the town as borderline desolate and poor, its richness is centered in the foundation of its community. The Cabecar people are Costa Rica’s largest indigenous population as approximately 10,000 members call this country home. This being said, only a few are seen in Quetzal as the majority of its inhabitants reside deep in the forest requiring a multi-hour walk to and from town in order to access life’s basics – food, supplies, and education.

Ricky’s brother Diego is a teacher at the indigenous high school in Quetzal so we were fortunate enough to visit him for a night. After a long drive to Quetzal (passing by Bajo Pacuare where the upper-upper section of the Pacuare River flows) we arrived shortly before lunch. We waited for the students to finish their lunch break and then joined them for an afternoon class. Fortunately for us, the day of our visit the students had a cultural presentation planned so we were able to experience firsthand a traditional Cabecar celebration.

Ricky and I had the pleasure of watching the students perform the act of civil which comprised of a reading, song, and dance complete with typical costumes. After the presentation, the teachers invited the students to share bombas which are jokes in the form of rhyming paragraphs. The bombas had the entire classroom in hysterics, and the student who stole the show was a teen by the name of Roger. Roger couldn’t be more than 17 years old (although he sported a hefty, mature mustache suggesting otherwise) and he wore a black hoodie with the word “borracho” (drunk) spread across the front. He was clearly one of the most popular kids in the class – his ability to have the entire group hanging on his every word and anxiously awaiting his next bomba fueled his likeability amongst his peers.

Ricky and I spent the rest of the afternoon exploring the high school, listening to the school band practice for an upcoming festival performance, and taking photos of the area. Diego informed us of ongoing school projects and showed us the guest house where some students sleep during the week since their homes are a day’s walk from the school. These students are able to stay in Quetzal during the week before returning home to their families on the weekend.

Approaching time for dinner, Ricky and I made our way to the cafeteria – a small, classroom-sized room with picnic tables in the front and a kitchen in the back. By this time, the majority of the students had left for the day and the school’s only inhabitants were Diego, two other teachers, Ricky, myself, and a handful of students bunking in the guest house. In the cafeteria we found Roger – the quick-witted student we had heard from earlier in the day. He was one of the students whose family lived far from the school, and although he would be retreating to the guest house later in the evening to rest with the other students (all students – male and female – bunk together), at the moment that we found him he was alone. I noticed him drawing something and I asked if I could look at his work. He shared it with me willingly, and to say the least, it was an incredible piece of art. Roger also spoke to me in Spanish and English – an impressive accomplishment given that approximately half of the Cabecar population speak and understand only their native indigenous tongue.

Music in the cafeteria provided a comfortable environment for Ricky and I to relax in while we watched Roger create his masterpiece. He knew (and quietly sang under his breath) the lyrics to nearly every hit song that played – Bryan Adams’ ‘summer of 69’, Avril Lavigne’s ‘what the h*ll’ and too many Green Day songs to count. He sat and worked so quietly, but his concentration was incredibly loud. It caused us to spend nearly an hour watching the drawing come to life.

The picture that emerged was beautiful, but equally as breathtaking was the learning opportunity that Ricky and I had been given to experience the Cabecar way of life. We truly appreciated our time at the school, especially that spent with Roger. Through an unveiling of similar tastes in music, a recognizable shared love for art, and an evening spent together at a picnic table, he taught us that although culture identifies difference, it certainly does not make us different. Instead, despite the notable differences that we spotted between the Cabecar way of life and our own (there are too many to list here), our visit to Quetzal informed us of countless ways in which we (non-indigenous and indigenous individuals alike) are the same. We love to laugh, joke, create, and enjoy. We have loud moments and quiet moments. Our interests, preferences, and emotions – the roots of who we are – although certainly shaped by our culture are indeed 100% our own. And in the end, we all just want to be loved and accepted for who we are.

Upon returning home from Quetzal I asked Ricky what he learned from the overall experience. He responded that we must never forget how little other people have, while at the same time never fail to appreciate how happy many people are with less. This statement did not surprise me, as Ricky is already the most humble person I know – one of about 4.5 million other Costa Ricans who live the simple life and are proud to do so. His comments reminded me that humility exists in the eyes and the hands of the beholder, and that one’s ability to view life as rich has little to do with one’s wealth.

For me, the visit to Quetzal taught me a lot about how we (society in general) regularly search for differences as a way of maintaining gaps between individuals and/or groups. First, we had tolerance for others who were different than us (‘us’ referring to whichever group you identify with). Next was acceptance (a more sensitive, humane, and empathizing form of tolerance) which aimed to remove some of the negative undertones of simply tolerating difference. Today, perhaps it can be said that diversity is no longer just tolerated or accepted, rather it is respected and celebrated (surely, one of the best approaches to difference there has been in our history). However, I cannot help but wonder how the world would be a different place if everyone began identifying with one another based on our similarities as opposed to categorizing each other based on our differences.

I’ll painfully admit it. When I first met Roger, it was his boisterous bomba jokes and ‘drunk’ sweatshirt that caught my attention. So did the sparse town we were surrounded by, the underdeveloped classroom we sat in, and the lack of school supplies and materials available to assist students in their learning. Surely, the school experience in Quetzal is one very different than that I remember having as a student many years ago, but apart from the material differences, the soul of the school and its students was the same. In fact, after the time Ricky and I spent with Roger, I could count more ways in which we could identify with the person he is and the life he lives than the ways in which we are different. The fact that he belonged to an indigenous tribe and we didn’t was not only irrelevant, but a point that skipped my mind entirely until I returned home and began reflecting on our visit.

In the end, Ricky and I learned different lessons as a result of the trip, but we left with a similar understanding – that although snap judgements can be habitual, they can also be overridden by a quality substance that resides beneath the surface of each individual. We must simply be open to uncovering this essence. Fortunately, the ability to do so is both geographically and culturally universal, is neither limited nor hindered by language, and is inside each of us. If we can only aim to connect with others on more profound levels (no matter how different an ‘other’ may appear) perhaps we can begin to close the gap between ‘us’ and ‘them’ and learn to relate to (not stray away from) one other.

*Discounts for tours to Costa Rica’s indigenous reserves are available through Pura Vida! eh? Incorporated at: http://www.puravidaeh.ca/

QUESTION TO COMMENT ON: Have you had a similar learning experience during your trip to Costa Rica or elsewhere? We’d love to hear about it!

Pura vida!

Hey, Costa Rica Travel Blog reader, thank you for visiting and reading our blog! We're truly grateful for your time and preference.

Do you know that your spam-free reading experience is most important to us? Unlike some other Costa Rica blogs, we do not to sell your personal information, and we choose not to display ads, sponsored content, or affiliate marketing on our blog so we can keep your visit as distraction- and junk-free as possible. Because we prioritize your privacy, we don't earn money when you visit us, when you sign up for our e-course, or when you click on our links, which means the time and work we put into this blog—including its 300+ articles—is entirely voluntary! If you find our content valuable, and you'd like to thank us for making the trip-planning process easier and your Costa Rica vacation more enjoyable, please consider making a small donation ($1, $2, $3, or an amount of your choosing) to our blog. Doing so is a great way to pat us on the back if you feel we deserve it. 😊 Pura vida, amigos!

Click on the button above to donate through PayPal. (If you cannot see the PayPal button above, click here.) A PayPal account is not required to make a donation; credit and debit cards are also accepted. PayPal donations are confidential; we never see your payment details.

Love our blog? Check out our other Costa Rica-related projects, too:

Tagged: costa rica, costa rica travel, costa rican culture, culture, humility, indigenous, pacuare river, peace, travel